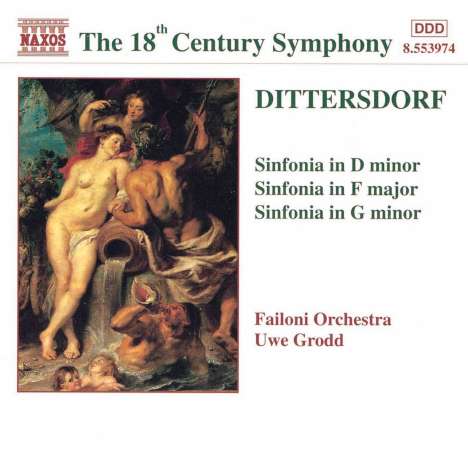

Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphonien d-moll,F-Dur,g-moll auf CD

Symphonien d-moll,F-Dur,g-moll

Herkömmliche CD, die mit allen CD-Playern und Computerlaufwerken, aber auch mit den meisten SACD- oder Multiplayern abspielbar ist.

(Grave d1, F7, g1)

- Künstler:

- Failoni Orchestra, Uwe Grodd

- Label:

- Naxos

- Aufnahmejahr ca.:

- 1996

- Artikelnummer:

- 8665478

- UPC/EAN:

- 0730099497428

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 7.9.1998

- Serie:

- Naxos 18th Century Classics

Weitere Ausgaben von Symphonien d-moll,F-Dur,g-moll |

Preis |

|---|---|

| CD | EUR 6,99* |

Die Sinfonia in d-Moll, die irgendwann zwischen 1773 und 1779 entstand, ist eine der beeindruckendsten Dittersdorfer Symphonien dieser Zeit. Eine Reihe österreichischer Komponisten, allen voran Haydn und Hofmann, experimentierten mit der Idee, eine Sinfonie mit einem ausgedehnten langsamen Satz zu eröffnen, aber die Praxis wurde relativ früh aufgegeben. Das ergreifende Adagio zu Dittersdorfs Sinfonie - in einigen Quellen unerklärlicherweise mit Andantino überschrieben - hat ein Gewicht und eine Intensität, wie man sie außerhalb von Haydns Sturm und Drang-Sinfonien selten findet. Die Bläser werden mit bezeichnender Wirkung eingesetzt, und Dittersdorfs raffinierte Melodielinien enthalten einige wunderbare und unerwartete harmonische Wendungen. Das überschwängliche Allegro vivace ist im Vergleich dazu ein viel geradlinigerer Satz. Seine starke, treibende Unisono-Eröffnung steht in krassem Gegensatz zu der leichten, huschenden Figur in den ersten Violinen und dem breiten, lyrischen zweiten Thema. Alle diese großen thematischen Bausteine tauchen im Mittelteil des Satzes wieder auf, aber anstelle der thematischen Entwicklung kommt Dittersdorf mit einer Überraschung: Die völlig unerwartete Gegenüberstellung von Themen und einer bemerkenswerte bedeutungsschwangere Pause. Das Minuetto und das Trio offenbaren den Komponisten in seiner schrulligen Bestform. Nicht nur verunsichert er den Zuhörer mit asymmetrischen Phrasenlängen und merkwürdigen Zwitschern der Bläser, sondern er beendet das Minuetto auch in der falschen Tonart und weist den Interpreten an, die erste Hälfte erst am Ende des Trios zu wiederholen. Das Presto non troppo-Finale, das um die Art von unwiderstehlichem Thema herum aufgebaut ist, dessen unumstrittener Meister Dittersdorfs Freund Haydn wurde, bringt die Sinfonie zu einem temperamentvollen Abschluss, der angesichts der düsteren Eröffnung des Werkes vielleicht etwas unerwartet kommt.

Die Sinfonia in g-Moll, eine der markantesten Moll-Tonartensymphonien Dittersdorfs, entstand spätestens 1768, in dem Jahr, als das große österreichische Benediktinerstift Lambach eine Abschrift erwarb. Die Sinfonie ist in sieben zeitgenössischen Quellen erhalten und wird auch in drei wichtigen thematischen Katalogen dieser Zeit aufgeführt: Lambach (1768), Breitkopf (Beilage VI 1772) und das Quartbuch (1775). Interessanterweise ist das Werk fast genau zeitgleich mit der frühesten von Haydns Sturm und Drang-Sinfonien, Hob. I: 39, die in derselben Tonart steht. Obwohl die beiden Werke in ihrem kompositorischen Ansatz sehr unterschiedlich sind, leben sie in einer ähnlichen Gefühlswelt.

Im Gegensatz zur Sinfonia in d-Moll, die den größten Teil der Zeit in der Durtonart spielt, behält die g-Moll-Sinfonie ihre turbulenten Qualitäten fast durchgehend bei. Selbst das zentrale Andante ist nicht ohne Spannungen, und vielleicht der einzige Punkt echter Ruhe ist das entzückende Trio mit seiner schimmernden Soloflöte, die die Celli verdoppelt. Wenn diese Intensität in der Sinfonie der Epoche auch ungewöhnlich ist, so manifestiert sich Dittersdorfs Experimentierfreudigkeit in einer noch neuartigeren Weise. Der Durchführungsteil des ersten Satzes führt auf einmal neues und scheinbar irrelevantes thematisches Material ein, das als Grundlage für die modulatorische Erweiterung dient. Die Logik dessen wird erst im Finale deutlich, wenn ein fast identischer Durchführungsteil auftritt, diesmal aber eindeutig auf der Grundlage des starken dreisätzigen Anfangsthemas. So erreicht Dittersdorf auf brillante Weise eine organische Einheit zwischen dem ersten und vierten Satz der Symphonie, nicht durch die Wiederverwendung früheren Materials im Finale, sondern durch die Vorwegnahme des Durchführungsteils des Finales im Kopfsatz. Doch damit sind die Überraschungen noch nicht zu Ende. Kurz vor dem Ende des Finales fällt die Musik in ein strahlendes G-Dur, angekündigt durch ein neues Thema, das seinerseits in eine kurze Coda mündet, die fast wie eine Apotheose auf dem Anfangsthema des Satzes basiert.

Product Information

The Sinfonia in D minor, written some time between 1773 and 1779, is one of Dittersdorf's most impressive symphonies of the period. A number of Austrian composers, foremost among them Haydn and Hofmann, experimented with the idea of opening a symphony with an extended slow movement but the practice was abandoned relatively early. The gripping Adagio opening to Dittersdorf's symphony – unaccountably headed Andantino in some sources – has a weight and intensity which is rarely found outside Haydn's Sturm und Drang symphonies. The wind instruments are used with telling effect and Dittersdorf's sophisticated melodic lines contain some marvellous and unexpected harmonic twists. The ebullient Allegro vivace, is, by comparison, a much more straight-forward movement. Its strong, driving unison opening contrasts starkly with alight, scampering figure in the first violins and the broad, lyrical second theme. All of these major thematic building blocks reappear in the central section of the movement but in place of thematic development Dittersdorf offers surprise: chiefly unexpected juxtaposition of themes and a notable pregnant pause. The Minuetto and Trio reveal the composer at his quirky best. Not only does he unsettle the listener with asymmetrical phrase lengths and odd chirrups from the wind instruments, but he also ends the Minuetto in the wrong key and directs the performer to repeat the first half only at the conclusion of the Trio. The Presto non troppo finale, built around the kind of irresistible theme of which Dittersdorf's friend Haydn became the undisputed master, brings the symphony to a spirited conclusion, one perhaps rather unexpected given the sombre opening to the work.

The Sinfonia in G minor, one of Dittersdorf’s most striking minor key symphonies, was written no later than 1768, the year the great Austrian Benedictine Monastery at Lambach acquired a copy. The symphony survives in seven contemporary sources and is also listed in three important thematic catalogues of the period: Lambach (1768), Breitkopf (Supplement VI 1772) and the Quartbuch (1775). Interestingly enough, the work is almost exactly contemporaneous with the earliest of Haydn's Sturm und Drang symphonies, Hob. I: 39, which is in the same key. Although the two works are very different in compositional approach they inhabit a similar emotional world.

Unlike the Sinfonia in D minorwhich spends the greater part of the time in the major mode, the G minor symphony retains its turbulent qualities almost throughout. Even the central Andante is not without its tensions and perhaps the only point of genuine repose is the delightful Trio with its shimmering solo flute doubling the cellos. If this intensity is unusual in the symphony of the period Dittersdorf’s penchant for experimentation manifests itself in an even more novel way. The development section of the first movement at once introduces new and seemingly irrelevant thematic material which serves as the basis for modulatory extension. The logic of this is not made apparent until the finale when an almost identical development section occurs but this time clearly based on the strong triadic opening theme. Thus, Dittersdorf brilliantly achieves an organic unity between the first and fourth movements of the symphony not by reusing earlier material in the finale but by anticipating the development section of the finale in the opening movement. But the surprises do not end there. Shortly before the end of the finale the music drops into a radiant G major, announced by a new theme, which in turn leads into a brief coda based on the opening theme of the movement almost in the manner of an apotheosis.

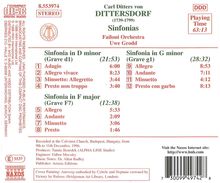

Disk 1 von 1 (CD)

-

1 Symphony in D minor, Grave d1: Adagio

-

2 Symphony in D minor, Grave d1: Allegro vivace

-

3 Symphony in D minor, Grave d1: Minuetto: Allegretto

-

4 Symphony in D minor, Grave d1: Presto non troppo

-

5 Symphony in F major, Grave F7: Allegro

-

6 Symphony in F major, Grave F7: Andante

-

7 Symphony in F major, Grave F7: Minuetto

-

8 Symphony in F major, Grave F7: Presto

-

9 Symphony in G minor, Grave g1: Allegro

-

10 Symphony in G minor, Grave g1: Andante

-

11 Symphony in G minor, Grave g1: Minuetto

-

12 Symphony in G minor, Grave g1: Presto con garbo

Mehr von Karl Ditters vo...

-

Karl Ditters von DittersdorfStreichquartette Nr.1,3-5CDAktueller Preis: EUR 7,99

-

Karl Ditters von DittersdorfStreichquartette Nr.2 & 6CDAktueller Preis: EUR 7,99

-

Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf6 Symphonien nach Ovids "Metamorphosen"2 CDsAktueller Preis: EUR 29,99

-

Karl Ditters von DittersdorfStreichquartette Nr.1,3-5CDVorheriger Preis EUR 19,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 9,99