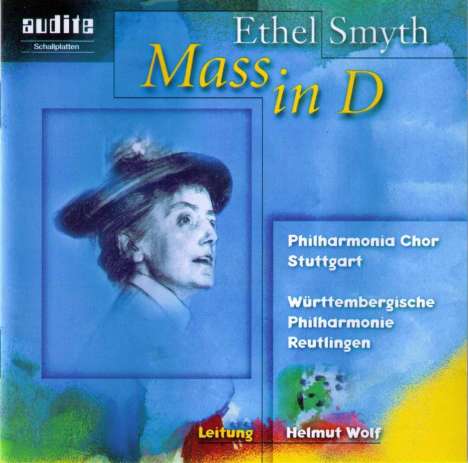

Ethel Smyth: Mass in D auf CD

Mass in D

Herkömmliche CD, die mit allen CD-Playern und Computerlaufwerken, aber auch mit den meisten SACD- oder Multiplayern abspielbar ist.

- Künstler:

- Smith, Schneidermann, Mac Allister, Macco, Württembergische Philharmonie, Wolf

- Label:

- Audite

- Aufnahmejahr ca.:

- 97

- Artikelnummer:

- 8330571

- UPC/EAN:

- 4009410974488

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 1.2.2007

Ethel Smyth wurde 1858 als Tochter eines britischen Generalmajors geboren. Im Geiste der viktorianischen Zeit erhält sie zu Hause und in einem Internat eine strenge Erziehung, gegen die sie immer wieder rebelliert. Gegen den Wunsch des Vaters erzwingt sie ein Musikstudium in Leipzig - Willensstärke und Ausdauer gehören zu ihren stärksten Charaktereigenschaften. In Leipzig ist sie enttäuscht vom verknöcherten Lehrbetrieb am Konservatorium, aber fasziniert von der Stadt, den Konzerten, den Begegnungen mit Brahms, Grieg, Clara Schumann. Heinrich von Herzogenberg unterrichtet sie privat, später auch Tschaikowsky. Kammer- und Klaviermusik entsteht, eine Serenade für Orchester bringt in England ersten Erfolg, der 1893 durch die Uraufführung der Messe, die das einzige geistliche Werk bleiben sollte, noch übertroffen wird. »Als ich jung war, stand ich - wie wir alle - im Bann der Oxford-Bewegung ich war hochanglikanisch, und als später der Glaube verflog, hatte dieser Aspekt des Anglikanismus niemals seinen Einfluss auf meine Phantasie verloren ... Um die Geschichte dieser Phase tiefsten Glaubens - Glauben im strengsten Sinne des Wortes - abzurunden, sollte ich sagen, dass ich in diesem und dem darauffolgenden Jahr eine Messe komponierte ... Alles, was in meinem Herzen war, legte ich in dieses Werk, aber kaum war es vollendet, wich der orthodoxe Glaube merkwürdigerweise von mir, um niemals zurückzukehren ... Wer soll den göttlichen Plan ermessen? Nur das will ich sagen: in keinem Abschnitt meines Lebens fühlte ich mich vernünftiger, weiser und der Wahrheit näher. Niemals war mir diese Phase - im Vergleich zu anderen, die darauf folgten - überreizt, unnatürlich oder hysterisch erschienen es war einfach eine religiöse Erfahrung, die in meinem Fall nicht von Dauer sein konnte.« Im Sommer 1891 suchte sie in ganz England nach einem Dirigenten, der kühn genug war, das große Chorwerk einer wenig bekannten Komponistin aufzuführen. Sie hatte das Gefühl, vor einer Wand zu stehen. Die angesehensten Komponisten der Zeit und Hüter der Tradition, Parry, Stanford und Sullivan, die sie persönlich kannte, rührten keinen Finger für sie. Unterstützung kam von einer ganz anderen, »unmusikalischen« Seite: Die französische Kaiserin Eugénie, Witwe Napoleons III., lebte in England im Exil und förderte Ethel Smyth, indem sie beim Verlag Novello die Herausgabe der Messe finanzierte und der Komponistin die Möglichkeit verschaffte, sich der Königin Viktoria vorzustellen und vor dem Hofstaat etwas aus der Messe vorzutragen. Sie wurde an einen riesigen aufgeklappten Flügel gesetzt und bot das 'Benedictus' und 'Sanctus' dar, » ... und zwar nach Art der Komponisten, das bedeutet: Man singt den Chor genauso wie die Soli und trompetet die Orchestereffekte heraus so gut es geht - eine geräuschvolle Prozedur ... Ermutigt durch die Klangfülle des Raumes, stimmte ich nun das 'Gloria' an - die leidenschaftlichste, und - wie ich dachte - die beste Nummer von allen. Als ein gewisser Trommeleffekt kam sogar ein Fuß ins Spiel, und ich vermute, zumindest was das Klangvolumen angeht, wurde die Anwesenheit eines richtigen Chores und Orchesters nicht vermisst! Diesmal, bestärkt durch die einfache und echte Anerkennung der Herrscherin, glaubte ich, einen Blick in die Gesichter ihres furchterregenden Hofstaates wagen zu können. Was machte es schon, wenn Erstaunen und heimliches Schockiertsein sich auf ihren Gesichtern abzeichneten? Ich saß jetzt tief im Sattel und war nicht so leicht herauszuheben! Ich blickte um mich. Sie waren phantastisch. Keine hochgezogene Braue, keinerlei Emotion! Es war ein derart aufregender, weil faszinierender Anblick, dass das Ergebnis ein Finale des 'Gloria' war, wie ich es mir bis dahin noch nie entrungen hatte!» Eineinhalb Jahre später, im Januar 1893 fand die Uraufführung mit etwa 1.000 Ausführenden in der riesigen, mit 12.000 Zuhörern besetzten Royal Albert Hall statt. Sie wurde begeistert aufgenommen. Auch bei dieser Aufführung stand das Gloria auf ausdrücklichen Wunsch der Komponistin als festliches Finale am Schluss der Messe. Fuller-Maitland, der Kritiker der 'Times' schrieb: »Dieses Werk stellt die Komponistin eindeutig unter die bekanntesten Komponisten ihrer Zeit, und mit Leichtigkeit an die Spitze all derer, die ihrem Geschlecht angehören. Was an der Messe besonders auffällt, ist das völlige Fehlen der Elemente, die man gemeinhin mit femininer Musik in Verbindung bringt es ist durchweg männlich, meisterhaft im Aufbau und in der Ausführung, und besonders bemerkenswert wegen der kunstfertigen und satten Färbung der Orchestrierung.« Dennoch verschwand das Werk von der Bildfläche und tauchte erst dreißig Jahre später wieder auf. »Mitte der zwanziger Jahre erinnerte ich mich - ich weiß nicht mehr, in welchem Zusammenhang - an die Messe, die niemals eine zweite Aufführung erlebt hatte, die nur von Graubärten gehört worden war und die ich praktisch vergessen hatte. Ein paar welke und verstaubte Klavierauszüge fanden sich auf einem oberen Regal, und nach intensiver Suche fand ich die gesamte Partitur auf meinem Speicher. Trotz des Urteils der Fakultät war das Werk augenscheinlich von den Mäusen gewürdigt worden, und als ich mich setzte, um es zu prüfen, teilte ich ihre Ansicht und entschied, dass es wirklich ein besseres Schicksal verdient hätte als 31 Jahre Scheintod. Aber als ich bei den Herausgebern die Möglichkeiten einer Wiederbelebung sondierte, war die Antwort: 'So sehr wir es bedauern: wir fürchten, Ihre Messe ist tot!'. Dieses Urteil spornte mich nur noch mehr an, und - um es kurz zu machen: 1924 fand eine brillante Aufführung in Birmingham unter der Leitung von Adrian Boult statt, die eine Woche später in London wiederholt wurde. Das Echo der Presse war diesmal überwältigend.« Kritischer äußert sich Ethel Smyth in einem Brief an eine Freundin über die Aufführung: »Im ganzen zufriedenstellend, aber du weißt ja, wie schwer ich zufriedenzustellen bin ... Warmherziger Empfang (für das fade Birmingham). Chor gut, Boult erstklassig, Orchester miserabel. Alle Posaunen wurden von Polizisten gespielt.« Die größte Freude aber hatte die Komponistin an einem Brief von George Bernhard Shaw, der bei der Uraufführung dreißig Jahre vorher bereits eine ausführliche, geistreiche und insgesamt sehr positive Kritik in »The World« veröffentlicht hatte. »Liebe Dame Ethel, - danke, dass Sie mich so lange tyrannisiert haben, bis ich mich aufgerafft habe, die Messe zu hören! Die Originalität und die Schönheit der Solopartien sind heute noch so beeindruckend wie vor 30 Jahren, und das übrige wird in der besten Gesellschaft Bestand haben. Großartig! Sie sind total und diametral im Unrecht, wenn Sie glauben, dass Sie unter einem Vorurteil gegen weibliche Musik gelitten hätten. Im Gegenteil: Sie wurden beinahe vernichtet durch die Ängste 'maskuliner' Musik. Es war Ihre Musik, die mich für immer von der alten Wahnvorstellung geheilt hat, dass Frauen auf dem Gebiet der Kunst und auch sonstwo keine Männerarbeit tun könnten. (Das war vor Jahren, als ich nichts über Sie wusste und eine Ouvertüre hörte - 'The Wreckers' oder so ähnlich -, bei welcher Sie ein großes Orchester auf dem Podium herumwirbelten.) Erst durch Sie habe ich mich mit der heiligen Johanna beschäftigen können, die früher jeden Dramatiker scheitern ließ. Ihre Musik ist männlicher als die von Händel... Ihr lieber großer Bruder G. Bernhard Shaw« Für diese Wiederaufführung 1924 überarbeitete die Komponistin das Werk. Die Veränderungen beziehen sich zum einen auf kleinere Verbesserungen im Chor- und Orchestersatz, zum anderen auf reduzierte, in den schnelleren Sätzen meist sogar erheblich langsamere Metronomzahlen, was sicher mit der Erinnerung an die Uraufführung mit ihrer riesigen Zahl von Ausführenden zusammenhängt. Unsere Aufnahme nähert sich hier wieder den ursprünglichen Vorstellungen der Komponistin an. Helmut Wolf Weitere Informationen zu Leben und Werk von Ethel Smyth erhalten Sie auf der Internetseite der Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg, Forschungsprojekt "Musik und Gender im Internet"

Ethel Smyth was born in 1858 daughter of a British general major. Being a child of the Victorian age she received a strict education at home and at a boarding school against which she revolted again and again. Against her fathers wish she managed to study music in Leipzig -strength of will and persistence were here strongest characteristics. In Leipzig she is disappointed with the ancient curriculum at the conservatoire but fascinated by the city, the concerts, the meetings with Brahms, Grieg and Clara Schumann. Heinrich von Herzogenberg gave her private lessons and also Tschaikowsky later on. She composed chamber- and pianomusic, a serenade for orchestra was her first success in England. In 1893 it was surpassed by the premiere of the Mass that remained her only religious work. Then she devoted herself to the opera. The most successful opera "The Wreckers", composed after a sinister Cornish legend was conducted by Bruno Walter, Arthur Nickisch and Sir Thomas Beecham. "When I was young, engrosses as we all were in the story of the Oxford Movement, I had been very High Church, and later when belief passed, this aspect of Anglicanism had never lost its grip on my imagination ... In order to round off the story of this phase of intense belief - belief in the strictest sense of the word - I ought to say that during this and the ensuing year I was composing a Mass ... Into that work I tried to put all there was in my heart but no sooner was it finished than, strange to say, orthodox belief fell away from me, never to return ... Who shall fathom the Divine Plan? Only this will I say, that at no period of my life have I had the feeling of being saner, wiser, nearer truth. Never has this phase, as compared to others that were to succeed it, seemed overwrought, unnatural, or hysterical it was simply a religious experience that in my case could not be an abiding one." In the summer of 1891 she searched all over England for a conductor who was daring enough to conduct the big choir composition of a quite unknown composer. She had the feeling as if she was standing up against a wall. The highly respected composers of that time and guardians of tradition, Perry, Standford and Sullivan, whom she knew personally, did not make any allowances to help her. She found support in a totally "unmusical" source: the French empress Eugenie, widow of Napoleon III, living in exile in England. She supported Ethel Smyth by financing the publication of the Mass at the Novello Press and by giving her the chance to introduce herself to Queen Victoria including the possibility to present a part of the Mass before her court. She was seated in front of a gigantic grand piano and performed the "Benedictus" and Sanctus as "... in the manner of composer that meant singing the chorus as well as the solo parts, and trumpeting forth orchestral effects as best you can, a noisy proceeding ... emboldened by the sonority of the place, I did the "Gloria" the most tempestuous and ... best number of all. At a certain drum effect a foot came into play, and I fancy that as regards volume of sound at least, the presence of a real chorus and orchestra was scarcely missed." One and a half year later, in January 1893 the premiere was held with about 1, 000 performers in the enormous Royal Albert Hall in front of an audience of 12, 000 people. It was received with enthusiasm. The "Gloria" was also performed as festive finale at the end of the Mass being the composer's utmost wish. Fuller-Maitland, a critic at Times wrote: "This work definitely places the composer among the most eminent composers of her time, and easily at the head of all those of her own sex. The most striking thing about it is the entire absence of the qualities that are usually associated with feminine productions throughout it is virile, masterly in construction and workmanship, and particularly remarkable for the excellence and rich colour of the orchestration" In spite of this the work vanished from sight to reappear again 30 years later. "In the middle twenties, I bethought me, I forget in what connection, of the Mass, which had never achieved a second performance, which none but greybeards had heard, and the existence of which I had practically forgotten. A couple of limp and dusty piano scores were found on an upper shelf, and after agitated further searchings the full score turned up in my loft. In spite of the judgement of the Faculty the work had evidently been appreciated by the mice, and on sitting down to examine it I shared their opinion, and decided that it really deserved a better fate than thirty-one years of suspended animation. But when I consulted the publishers as to the possibility of a revival, the reply was, 'Much as we regret to say so, we fear your Mass is dead'. This verdict stung me into activity, and to cut a long story short, in 1924 Adrian Boult produced it brilliantly in Birmingham and the following week in London. This time the press was excellent." Writing to a friend about the performance Ethel Smyth noted critically: "On the whole satisfactory, but you know how hard I am to please ... Audience warm (for stodgy Birmingham). Chorus fine. Boult first rate. Orchestra putrid ... All the trombones were played by policeman." The greatest pleasure Ethel Smyth had was in a letter from George Bernhard Shaw, who had been to the premiere of the Mass 30 years earlier and had a very detailed witty and altogether positive critic which had been published in "The World". "Dear Dame Ethel, - Thank you for bullying me into going to hear that Mass. The originality and beauty of the voice parts are as striking today as they were 30 years ago, and the rest will stand up in the biggest company. Magnificent! You are totally and diametrically wrong in imagining that you have suffered from a prejudice against feminine music. On the contrary you have been almost extinguished by the dread of masculine music. It was your music that cured me for ever of the old delusion that women could not do men's work in art and other things. (That was years ago, when I knew nothing about you, and heard an overture - "The Wreckers" or something - in which you kicked a big orchestra all round the platform.) But for you I might not have been able to tackle St Joan, who has floored every previous way playwright. Your music is more masculine than Handel's. Your dear big brother, G. Bernard Shaw." For this re-performance in 1924 she revised the composition. The changes refer to a small improvement in the choir- and orchestralparts and a reduction of the metronome beat most considerably in the fast movements. The changes are surely due to the remembrance of the premiere with its gigantic number of performers. Here our recording again approaches the original intention of the composer. Helmut Wolf

Rezensionen

...und zwischen viktorianischem Bombast finden sich unerwartet empfindsame Vokalsoli und kammermusikalisch fein instrumentierte Orchesterstellen. (Klassik heute)

Rezensionen

P. T. Köster in KLASSIK heute 5/98: "Zwischen vikto- rianischem Bombast finden sich unerwartet empfindsame Vokalsoli und kammermusikalisch fein instrumentierte Orchesterstellen."-

Tracklisting

-

Details

-

Mitwirkende

Disk 1 von 1 (CD)

Messe D-Dur (für Soli, Chor, Orchester und Orgel)

-

1 Kyrie

-

2 Credo

-

3 Sanctus

-

4 Benedictus

-

5 Agnus Dei

-

6 Gloria

Mehr von Ethel Smyth

-

Ethel SmythStreichquartett e-mollCDAktueller Preis: EUR 7,99

-

British Music for Strings Vol.3 (British Women Composers)CDVorheriger Preis EUR 17,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 7,99

-

Esther Abrami - WomenCDAktueller Preis: EUR 19,99

-

Ensemble Horizons - Unerhörte KomponistinnenCDAktueller Preis: EUR 16,99