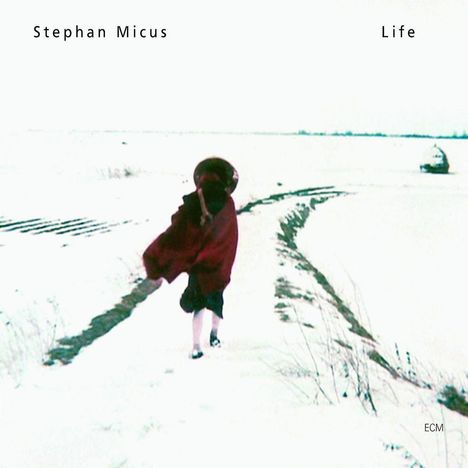

Stephan Micus: Life auf CD

Life

Herkömmliche CD, die mit allen CD-Playern und Computerlaufwerken, aber auch mit den meisten SACD- oder Multiplayern abspielbar ist.

- Label:

- ECM

- Aufnahmejahr ca.:

- 2004

- Artikelnummer:

- 1346848

- UPC/EAN:

- 0602498188118

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 22.8.2007

Since the early 1970s Stephan Micus has refined an eclectic musical vision that transcends both boundaries and borders in its global scope. The impressive body of work he has created in over thirty years of adopting, and often adapting, exotic instruments and making them part of his personal artistic worldview reveals a rare talent for overcoming what for most Westerners would be insurmountable obstacles to understanding and assimilating the grammar and vocabulary of a myriad of foreign musical languages. The genesis of “Life,”his 16th ECM album, can be traced back to his 1977 release “Koan” (a “koan” is a Zen Buddhist riddle used to show the student the limitations of the intellectual mind and serves as an aid to the development of intuitive action) and is based on his favorite “koan” where a monk and his master are discussing the meaning of life. Recorded between 2001 and 2004 in his studio on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, “Life” is an elaborate 10-part, 53-minute composition that tells this riddle using instruments from such diverse countries as Ethiopia, Egypt, Ghana, India, Tibet, Indonesia, Burma, Thailand, Japan, Ireland and Germany. All the vocal parts are performed by Micus himself, singing the text in the original Japanese. “The challenge in creating this work was how to best present in a musical composition a riddle that starts and ends with the same answer,” Micus said when asked about “Life.” “What’s so wonderful about this riddle is its symmetry but I didn’t want to repeat the same music from the beginning of the piece at the end so I had to come up with a solution,” he explained. “I ended up developing the composition in an unusual way that moves from complexity to simplicity, the exact opposite of how most compositions, including my own, are usually constructed,” he continued. “After I realized that the only way for me to intelligently distinguish between the riddle’s two identical answers was to move in the opposite direction of a traditional piece of music, everything else fell into place. The long first section, ‘Narration One And The Master’s Question,’ is very complex, more than any other piece I’ve ever written. I spent a long time working on it, laying down nine instrumental and eleven vocal tracks. Yet by the time we arrive at the final section, ‘The Master’s Answer,” all we hear is a solo human voice. The work’s transition from complexity to simplicity represents a kind of evolution to me and I view the composition as a musical analogy for how some people, if their life experiences have helped them become more aware, end up transforming the way they lead their lives. That’s why I named the piece ‘Life.’”

The multicultural set of instruments Micus plays on “Life” includes Balinese gongs, Bavarian zithers, Thai singing bowls, Tibetan chimes and cymbals, Japanese mouthorgans, Irish tin whistle, Ghanese drums, the Egyptian “nay,” and the Indian “dilruba” as well as two he has recorded here for the first time: The “maung,” a set of forty tuned bronze gongs from Burma, and the “bagana,” an ancient Ethiopian lyre traditionally played in private to accompany prayer and meditation that, according to Micus, is on the list of endangered instruments threatened with extinction within a generation or two.

Also known as the “Harp of David” (it was allegedly played by David to sooth King Saul’s insomnia), legend says the bagana was imported to Ethiopia from Israel thousands of years ago by Menelik I, the nation’s first Emperor and the son of King Solomon and Makeda Queen of Sheba. The tall lyre consists of a large, square wooden sound box covered with sheep skin connected to a frame strung with strings traditionally made from sheep’s intestines. Leather thongs placed between the strings and the bridge produce its characteristic buzzing sound. “I went to Addis Ababa in January of 2000 to study the bagana with Alemu Aga, a master musician and one of the very few people who can still play this instrument that will probably disappear soon. It is traditionally played by the singers of religious texts of the ancient Ethiopian Orthodox Church”, Micus explained. “The bagana has ten strings but they use only five which I found very strange. When I asked my teacher why the other strings were not played he replied ‘we forgot how those five were tuned.’ As I frequently do, I modified the instrument and on this recording I used all ten strings that I gave new tunings. I also experimented with techniques like playing it with a bow and with mallets in a percussive manner.”

In giving the bagana the most prominent role on “Life,” Micus has written and played what is conceivably the first modern music for it (not to mention created a context where a sacred Judeo-Christian instrument can coexist with ones from the world’s two other main religions - the nay of Islam and the gongs of Buddhism). The ancient lyre is only featured on five pieces of “Life,” but its somber sound haunts the recording and provides the sober mood that permeates Micus’s composition that traces the circuitous route of a monk who leaves his monastery and his master on a quest to discover the meaning of life, only to end up where he began and learn that the answer to his question remains the same. Mitchell Feldman

Stephan Micus is a man to be envied. Whereas ordinary mortals have just one life, he seems to lead three different ones all at the same time: one to travel, another to study and learn and a third to record a whole string of CDs of his own compositions. And he does all this without losing any of his tranquillity. His music is resounding proof of that.

Many of his instruments, most originating from Asia and Africa, represent age-old music traditions that are in danger of dying out. Viewed in this light, Micus' compositional oeuvre can be regarded as the Noah’s Ark of sound. His music has lost none of its innocence, but has gained much in terms of wisdom. His solitary lifestyle and tendency to work alone have enabled him to develop his own very distinctive sound, averse to any whims of fashion. Stephan Micus deserves a place of honour among contemporary composers, a laurel wreath for his passion for experimentation and a deep bow for his solo craftsmanship. Parool, Netherlands

When encountering the music of another culture, most Western musicians adapt by learning to play the instruments native-style and mimicing the music of that culture. But from the very beginning, Micus had his own direction and his own voice. He created his own very distinctive music, and though he used acoustic instruments from many cultures, he did it in ways they never dreamed of – rebuilding instruments, changing tunings, and playing them in idiosyncratic ways. And famously, he mixed instruments from around the world, or used whatever was at hand: stones, ordinary flowerpots tuned with water, and his voice – singing non-verbal improvised sounds over ten years before others made this approach fashionable. The Hearts of Space US nation-wide radio program

This extraordinary multi-instrumentalist is actually one of the few to have grasped in its essence what was the song of the world. With him there exist no territories or cultural atavisms, but a planetary polyphony projected on a horizon of eternity. His instruments exchange once more the out-lines of their countries of origin to become instruments without nationality in the hands of this nomad musician. Exceptional. Keyboards, France

Micus's music possesses gossamer beauty. Timeless, magical music with a universal appeal. The Times, UK

Listening to the music of Stephan Micus – which is as itinerant and wide ranging as his life – is one of the most profound experiences possible today. Beyond categories and labels, this German artist was already way ahead of trends when he released his first album in 1976. Fifteen recordings later The Garden of Mirrors, his first CD since the phenomenal Athos, seems on the surface to be heading in a stylistic direction pointing towards the Orient. But upon further listening it’s clear Micus is exploring an internal universe governed by natural elements on the one hand and, paradoxically, by silence on the other. “Passing Cloud”, “Gates of Fire” and “Words of Truth” are the titles Micus uses to name pieces that elaborate his personal liturgy and interpret the movement of water and wind, the flight of clouds and the voices of the spirit. An intrepid traveller and perpetual student, he has learned to play ancient and rare traditional instruments that are as evocative as they are esoteric. When he sings he sounds like a chanting mystic in a trance. The Garden of Mirrors is a recording to be experienced the way one would a journey, the type of voyage Bruce Chatwin would describe as “looking inward”. La Repubblica, Italy

The music of Stephan Micus is something completely new and entirely ancient and al-together embracing of humankind. If it isn’t heaven, it sounds somewhere near it. Detroit Free Press, USA

A solemn music, at first enigmatic, then slowly revealing itself. The more one listens – really listens –, the more the music absorbs one. Die Zeit, Germany

… remarkable, haunting and truly timeless. Down Beat, USA

Before there was world music, there was Stephan Micus, playing instruments from Afghanistan, India, and Indonesia. But ever since his first album (released in 1976) the German composer has not been making world music but other – worldly music. He plays ethnic instruments in nontraditional ways, multitracking them in layered arrangements and creating meditative excursions. Stephan Micus isn’t pan-cultural but transcends culture with music that’s innocent but not naive. Billboard, USA

Fascinating music, where silence has its place. Midi Libre, France

Micus has a natural aptitude for taking ethnic sounding instruments and playing them in a manner that places them outside their traditional context. Sounds, England

Wistful, sweet-sad melodies, warm, glo-wing chords, shadows become sound; strands of light are tuned and strummed … a truly original voice, suffused with a mysticism that is equal parts Western and Eastern. Rolling Stone, USA

The interesting sounds of these unusual instruments contrast strongly with the thoughtless imitative monotony of the synthetic sounds which are delivered to our houses in such great quantity by the pop in-dustry. It becomes clear, however, that it is not possible to imitate everything. Micus himself does not imitate. He takes inspirations – from the Far East for example – and transforms them into his own quite Euro-pean music. Frankfurter Rundschau, Germany

A music full of dignity, speaking about the understanding of life. The vocal sections are reminiscent of Gregorian chanting, Nomad songs and Japanese monks reciting sutras. This enigmatic musician manages to unite elements from Europe, the Middle East, and the Far East into a synthesis which explores the relationship between emptiness and form. Swing Journal, Japan

Micus' style of singing is comparable to a universal language, to a transcultural code, as if participating in all languages and transcending them at the same time. Basler Zeitung, Switzerland

Stephan Micus is inspired and abandoned, unself-conscious and disciplined all at once, producing dazzling sound and exquisite melodies. It’s ancient-sounding, witchcraft kind of music, music that’s innovative and entirely contemporary in its disturbing directness, a work of genius indeed, a unique talent, a painter of soundscapes, one of Europe’s strongest and most original soloists. Fanfare, USA

Tracklisting

Disk 1 von 1 (CD)

-

1 Narration one and the master's question

-

2 The temple

-

3 Narration two

-

4 The Monk's answer

-

5 Narration three

-

6 The master's anger

-

7 Narration four

-

8 The monk's question

-

9 The sky

-

10 The master's answer

Mehr von Stephan Micus

-

Stephan MicusMusic Of StonesCDVorheriger Preis EUR 16,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 15,99

-

Stephan MicusDesert PoemsCDVorheriger Preis EUR 16,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 15,99

-

Stephan MicusTowards The WindCDVorheriger Preis EUR 16,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 15,99

-

Stephan MicusSnowCDVorheriger Preis EUR 16,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 15,99