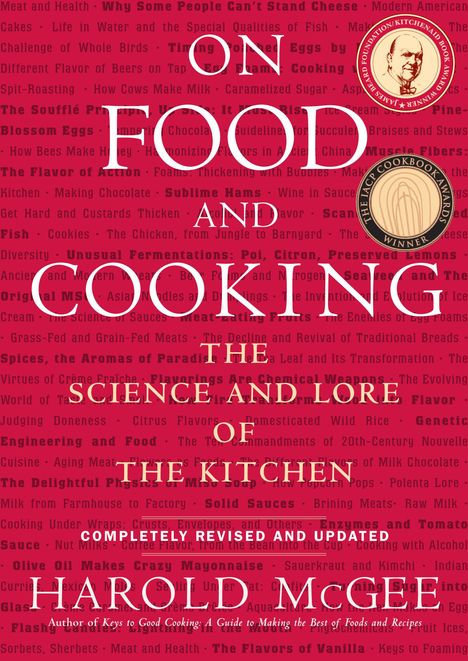

Harold J. McGee: On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, Gebunden

On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen

- The Science and Lore of the Kitchen

(soweit verfügbar beim Lieferanten)

- Illustration:

- Patricia Dorfman, Justin Greene

- Verlag:

- Scribner Book Company, 11/2004

- Einband:

- Gebunden, ,

- Sprache:

- Englisch

- ISBN-13:

- 9780684800011

- Artikelnummer:

- 2371276

- Umfang:

- 884 Seiten

- Ausgabe:

- Revised and Updated edition

- Copyright-Jahr:

- 2004

- Gewicht:

- 1379 g

- Maße:

- 244 x 180 mm

- Stärke:

- 48 mm

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 23.11.2004

- Hinweis

-

Achtung: Artikel ist nicht in deutscher Sprache!

Inhaltsangabe

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Cooking and Science, 1984 and 2004

Chapter 1 Milk and Dairy Products

Chapter 2 Eggs

Chapter 3 Meat

Chapter 4 Fish and Shellfish

Chapter 5 Edible Plants: An Introduction to Fruits and Vegetables, Herbs and Spices

Chapter 6 A Survey of Common Vegetables

Chapter 7 A Survey of Common Fruits

Chapter 8 Flavorings from Plants: Herbs and Spices, Tea and Coffee

Chapter 9 Seeds: Grains, Legumes, and Nuts

Chapter 10 Cereal Doughs and Batters: Bread, Cakes, Pastry, Pasta

Chapter 11 Sauces

Chapter 12 Sugars, Chocolate, and Confectionery

Chapter 13 Wine, Beer, and Distilled Spirits

Chapter 14 Cooking Methods and Utensil Materials

Chapter 15 The Four Basic Food Molecules

Appendix: A Chemistry Primer

Selected References

Index

Rezension

"I know of no chef worth his salt who doesn't keep a copy of Harold McGee's masterwork, On Food and Cooking. ..Simply put, it is the Rosetta stone of the culinary world...McGee flipped on the science switch, and suddenly there was light. Whereas Julia Child taught "how," McGee explains 'why.'" - Alton Brown, Time

Klappentext

Harold McGee's On Food and Cooking is a kitchen classic. Hailed by Time magazine as "a minor masterpiece" when it first appeared in 1984, On Food and Cooking is the bible to which food lovers and professional chefs worldwide turn for an understanding of where our foods come from, what exactly they're made of, and how cooking transforms them into something new and delicious.

Now, for its twentieth anniversary, Harold McGee has prepared a new, fully revised and updated edition of On Food and Cooking . He has rewritten the text almost completely, expanded it by two-thirds, and commissioned more than 100 new illustrations. As compulsively readable and engaging as ever, the new On Food and Cooking provides countless eye-opening insights into food, its preparation, and its enjoyment.

On Food and Cooking pioneered the translation of technical food science into cook-friendly kitchen science and helped give birth to the inventive culinary movement known as "molecular gastronomy." Though other books have now been written about kitchen science, On Food and Cooking remains unmatched in the accuracy, clarity, and thoroughness of its explanations, and the intriguing way in which it blends science with the historical evolution of foods and cooking techniques.

On Food and Cookingis an invaluable and monumental compendium of basic information about ingredients, cooking methods, and the pleasures of eating. It will delight and fascinate anyone who has ever cooked, savored, or wondered about food.

Auszüge aus dem Buch

Introduction: Cooking and Science, 1984 and 2004

This is the revised and expanded second edition of a book that I first published in 1984, twenty long years ago. In 1984, canola oil and the computer mouse and compact discs were all novelties. So was the idea of inviting cooks to explore the biological and chemical insides of foods. It was a time when a book like this really needed an introduction!

Twenty years ago the worlds of science and cooking were neatly compartmentalized. There were the basic sciences, physics and chemistry and biology, delving deep into the nature of matter and life. There was food science, an applied science mainly concerned with understanding the materials and processes of industrial manufacturing. And there was the world of small-scale home and restaurant cooking, traditional crafts that had never attracted much scientific attention. Nor did they really need any. Cooks had been developing their own body of practical knowledge for thousands of years, and had plenty of reliable recipes to work with.

I had been fascinated by chemistry and physics when I was growing up, experimented with electroplating and Tesla coils and telescopes, and went to Caltech planning to study astronomy. It wasn't until after I'd changed directions and moved on to English literature -- and had begun to cook -- that I first heard of food science. At dinner one evening in 1976 or 1977, a friend from New Orleans wondered aloud why dried beans were such a problematic food, why indulging in red beans and rice had to cost a few hours of sometimes embarrassing discomfort. Interesting question! A few days later, working in the library and needing a break from 19th-century poetry, I remembered it and the answer a biologist friend had dug up (indigestible sugars), thought I would browse in some food books, wandered over to that section, and found shelf after shelf of strange titles. Journal of Food Science. Poultry Science. Cereal Chemistry. I flipped through a few volumes, and among the mostly bewildering pages found hints of answers to other questions that had never occurred to me. Why do eggs solidify when we cook them? Why do fruits turn brown when we cut them? Why is bread dough bouncily alive, and why does bounciness make good bread? Which kinds of dried beans are the worst offenders, and how can a cook tame them? It was great fun to make and share these little discoveries, and I began to think that many people interested in food might enjoy them. Eventually I found time to immerse myself in food science and history and write On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen.

As I finished, I realized that cooks more serious than my friends and I might be skeptical about the relevance of cells and molecules to their craft. So I spent much of the introduction trying to bolster my case. I began by quoting an unlikely trio of authorities, Plato, Samuel Johnson, and Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, all of whom suggested that cooking deserves detailed and serious study. I pointed out that a 19th-century German chemist still influences how many people think about cooking meat, and that around the turn of the 20th century, Fannie Farmer began her cookbook with what she called "condensed scientific knowledge" about ingredients. I noted a couple of errors in modern cookbooks by Madeleine Kamman and Julia Child, who were ahead of their time in taking chemistry seriously. And I proposed that science can make cooking more interesting by connecting it with the basic workings of the natural world.

A lot has changed in twenty years! It turned out that On Food and Cooking was riding a rising wave of general interest in food, a wave that grew and grew, and knocked down the barriers between science and cooking, especially in the last decade. Science has found its way into the kitchen, and cooking into laboratories and factories.

In 2004 food lovers can find the science of co